What is Civic Tech?

Civic tech is a big word. It’s a rally cry. A buzzword. A brand. It’s a trend many of us want to be part of, but we can’t agree on what it is. Civic tech is squishy. Sometimes it is defined in terms of markets, dependant on who the customers are, how old the provider is, or what sector either belongs to. Sometimes, it is defined in terms of products, based on the class of problem a tool addresses, the features it has, or the technologies it uses.

Here, we would like to lay out what Open Twin Cities means and believes when we discuss “civic tech”.

“Civic Tech”

So, what is “civic tech” for Open Twin Cities?

Civic tech is a set of processes involving deep engagement with diverse stakeholders for creating effective tools in support of the public good.

There is a lot packed into this one sentence. Let’s take some time to dig into these words.

Civic tech is a set of processes…

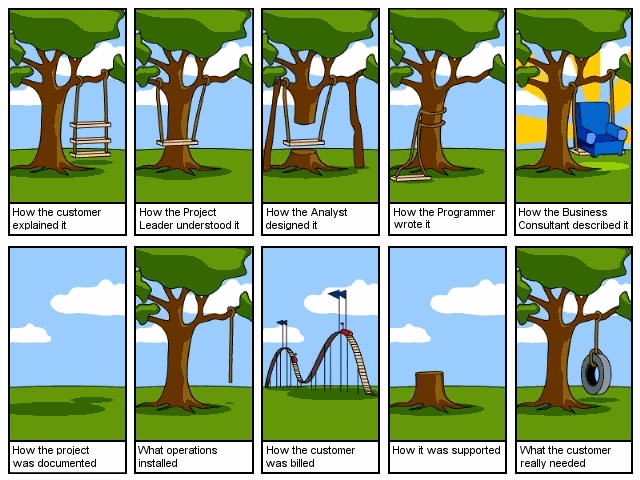

“Technology” is the most tangible aspect of civic tech. But, like all technologies, the tools created in the name of civic tech are really just an artifact of a process; the result of people and groups organizing, setting a strategy, and executing. We start this definition with ‘process’ because, despite all the attention bestowed upon specific apps and websites, it is ultimately the processes used to create and maintain those tools, and the processes that those tools are embedded in, that determine how successful those tools are. Civic technology works in the realms of “agile development”, “service design”, “human centered design”, and “procurement” because those of us in the civic tech world have come to understand that these and related processes need to be employed and improved in order to create the “best” technologies.

Poor processes yield poor tools that stubbornly keep people away from what they need and want. Good processes yield good tools that respond to the ever changing world to connect people with what they need and want.

…involving deep engagement with diverse stakeholders…

Put another way, Build With, Not For.

Innovation is more likely to occur when disparate groups discuss. New ideas occur when fresh perspectives look at a topic, or when conversations happen among those who do not usually talk. Groups and individuals learn more about each other. They better understand each other’s motivations, needs, and assets. This deep engagement is where true collaboration starts, as disparate groups learn to work together and co-create solutions to the problems they face.

Civic tech works on services with a wide range of providers serving an incredible variety of individuals. This provides an incredible opportunity to build partnerships, create dialogue among many perspectives, think ideas not possible in isolation, and empower all to take part in creating solutions.

In order to produce tools that best support these services, civic technology requires this opportunity be employed to the greatest extent possible. For not only does deep engagement yield new connections and ideas, it also produces the conversations across groups that are required for good and effective tools to be created.

The creation of tools is filled with stated and unstated biases; known and unknown questions with known and unknown answers distributed among a myriad of different groups. Tools often fail at their intended tasks because the processes that created them failed to allow or encourage these groups to communicate and coordinate, resulting in tools built on assumptions, unanswered questions, and unasked questions.

It is for this reason that the human centered and service design philosophies place such an emphasis on communication, collaboration, and feedback among all of the parties impacted by or impacting a tool. Further, these design philosophies carry this emphasis beyond just the creation of tools - all aspects of delivering a service are on the table for discussion, from the scope of the problem to the development, delivery, maintenance, and iterative improvement of a service.

New relationships. New ideas. Feedback. This is the democratization of public tool development. To me, this is the most important element of civic tech.

…for creating effective tools…

Poor tools stubbornly keep people away from what they need and want. Good tools respond to the ever changing world to connect people with what they need and want.

While we are aware that tools are but a part of a larger system connecting people with services and each other, we also recognize the impact the quality of these tools can have on that connection. The brief history of public services on the Internet is replete with examples of poorly constructed tools that have prevented people from connecting with their governments or obtaining needed services - from the much maligned federal and state health care exchanges to the obtuse general local government websites to public service websites that are unusable on a mobile device. Behind all of these examples are stories, in some cases thousands or millions, of people who spent countless hours accessing services that should have taken minutes, or of people who gave up due to fatigue or technical errors. Conversely, well designed tools can greatly ease the burden of connecting with government and help individuals discover services they never knew existed.

Creating effective tools relies on the processes and deep, diverse engagement already discussed. Through collaboration among different perspectives, these processes help to define shared goals, implementation needs, and novel strategies. These processes help to identify what works and what doesn’t. All this leads to service initiatives that are more successful because they make use of tools that more effectively support the goals, needs, and strategies of the service and its users.

…in support of the public good.

As Lawrence Grodeska recently stated, a project can not be ‘civic technology’ unless it intends to improve the public good. But what is ‘the public good’? The vague and contentious nature of ‘public good’ makes the deep and diverse engagement discussed earlier all the more important. Ultimately, the community at large must discuss and decide what the ‘public good’ is, and whether a given service benefits it.

Knowing that only the community can decide what the ‘public good’ is, we’ll offer a loose definition of projects that serve the public good as projects that aim to improve social justice or provide services that support important social priorities. While local government is very likely to play a role in such projects, it is worth noting that many non-profit and for-profit organizations also support the public good, and that projects from these sectors or that work with these sectors may fit within ‘civic tech’.

Thank you to Alison Link and Kelly Clausen, and Steve Clift for your input and edits.

2016-01-15 Update

The original version of the civic tech definition referred to ‘public service’. This has been updated to refer to the more general term ‘public good’.

2016-02-24 Update

Shu Higashi of Code for Japan has translated this article into Japanese!